Submitted By: Korrin L. Bishop, Co-founder & President (This piece first appeared on The Good Men Project)

I watched it play out several times before my departure. I’d explain my plans to kayak solo for a week through the backcountry of Everglades National Park to various father-daughter and boyfriend-girlfriend pairs. The conversations always ended the same. The father or boyfriend would turn to the daughter or girlfriend, and say, “I’m definitely never letting you do something like that!”

There was a lot about these interactions that made me cringe. Each conversation perpetuated the dialogue that men can be safe in the wild, but women can’t, and that women need permission to do something on their own.

However, while these dialogues made me cringe, I also felt deep compassion for these men. They were, after all, men who truly cared about the women in their lives. Not to mention, it’s not like my own dad had immediately vocalized an excitement over my plans. In fact, he sort of just went silent about it. I knew he had to process it.

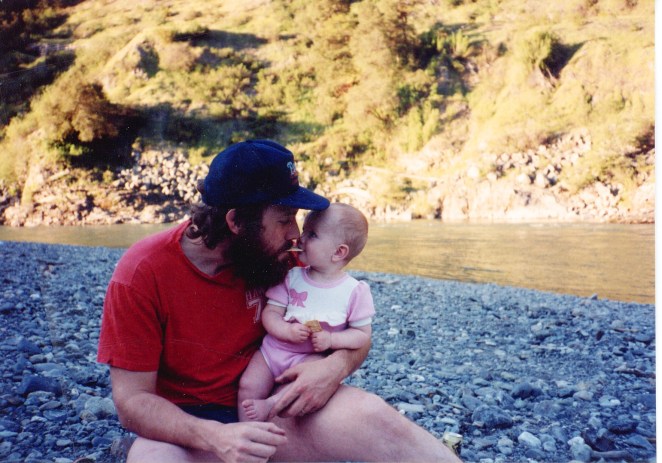

Since college, my dad and I have written letters to each other in a journal we mail back and forth. We’re currently on our third volume of letters. The letters are filled with life philosophies, family history, random rambles, social justice rants, current events and personal processing of when we’ve each had to come to grips with major changes in each other’s lives.

After an initial period of silence, of avoiding the topic of the Everglades in our conversations altogether, my dad wrote to me:

I am filled with trepidation about your kayak trip. But I “see” you. I have the usual fears about you being out there alone. But I’m sure it will be OK.

You’re a big spirit. You have to go. I have hiked into the wilderness alone twice now. Both times it was more and less than my fantasy about it.

There is plenty of time while backpacking where you are just grinding. Trudging up a ridge. Bandaging your blisters. Sometimes you’re so tired you don’t notice how amazing where you are is.

But then you are surrounded by it and it takes you. The vastness and wildness. The beauty. The wildlife.

I always have a craving to go back to the wilderness. You purposefully push yourself and see that you are capable of persevering through the physical and mental challenges of being alone in the wild.

I know you have to go. I respect that you are that kind of person. One who needs to go and be with yourself and the wild. Mark my words, whatever lies ahead for you will be meaningful. So, go on your trip with my blessing, and perhaps a cash donation.

There is always risk. Prepare best you can. But life is to be lived, not feared. Go forth and trip. But call me as soon as you’re out of the wild so I can relax again.

Like the fathers and boyfriends I encountered while talking about my trip, my dad had the same fears and protective spirit. When I read his letter, I felt the powerful love driving those reactions, but I also felt immense gratitude for him channeling those emotions not toward restricting my life, but toward championing it. With his honest blessing, I didn’t feel small and incapable; I felt confident and empowered.

To assuage my father’s fears, I took an emergency satellite communicator with me. The device periodically pinged my location to an online map. I appreciated that I didn’t have to do anything, but turn it on, so I could still feel disconnected from the outside world. My dad appreciated that he’d be able to see my little dot still moving forward each day.

I paddled out on my first day with excitement. I was ready.

Halfway through my first day’s paddle, my kayak’s rudder fell off. It hung from its strings, dangling in the water behind me.

When I got to my campsite that evening, I examined it. I didn’t have the tools needed to fix it. I’d just have to do without. I strapped the rudder onto the top of my kayak so that it would stop dragging behind me the next day, set up camp, cooked dinner and basked in the park’s beauty.

That night, I slept with a knife in one hand and a flashlight in the other when all of the sounds of the dark came out to play.

The second day, I awoke and took in the light of morning, leaving a little later than planned.

After a brief, winding creek, I entered a calm cove of brackish water, and felt cradled in the arms of Mother Earth. This section was called Sunday Bay, but in my mind I kept mistaking its name as God’s Bay. In the middle of this vast, natural stillness, I looked up at the stunning, blue sky, and felt the spiritual presence of a Heavenly Father.

Gently held between the arms of my Mother Earth and the protecting gaze of my Heavenly Father, I paddled on, becoming increasingly aware of the extra effort it was taking to paddle without a rudder.

A series of large bays later, I got tired. The two-dimensional plane of mangroves blended together in my vision, and the channel I was on that should’ve been widening was narrowing. Realizing my mistake, I backtracked to paddle down another channel only to end up circling an island and heading back down the way I’d come.

I was getting hungry and thirsty and could see the sun quickly descending in the sky. I knew I was still at least four miles away from camp. Alone in the wilderness, I began singing “Amazing Grace,” not yet willing to admit I was lost. I was lost-ish, I told myself. I sort of knew where I was, but just didn’t exactly know where I was going.

Then hunger, thirst and exhaustion bred fear. I began thinking about my arms giving out on me. There was nowhere to dock. I’d have to tie up to a mangrove and sleep in my kayak.

At last, I pulled out my satellite communicator and pinged my dad my GPS coordinates and a sloppily typed, “Turned around. Help me out?” Then I looked up at the sky like I had in Sunday Bay, only this time I saw another father looking down at me with love and protection in his eyes.

It took a little time, but I heard back from him. His initial reply was even more jumbled than mine. His words were duplicated and misspelled and his directions were muddled.

I could feel his worry, so I sent a message back to get clarification and also say I was feeling OK. In reality, I felt like vomiting.

With his bird’s eye view, I confirmed where I thought I was, and decided to paddle toward a different campsite a couple miles closer. I had been in a moment of fight, flight, or freeze, and my body had wanted to resign, both physically and mentally, but the moment I paddled forward with confidence in my direction, I handed my fear over to faith, and felt strong again—stronger even.

A dolphin greeted me as my campsite came into view. I pinged my dad my safe arrival, and smiled wide. I imagined him back home pouring himself a drink and filling with pride over a well-executed, technical rescue, of sorts.

That evening, I had a fortuitous encounter with a righteous ranger on the evening patrol. After checking my permits and confirming I had a proper personal flotation device, he caught a glimpse of my mangled rudder.

“How’s your rudder doing?” he asked.

“Um, not good. It’s broken,” I replied, giggling inside over our shared, yet unspoken sarcasm of the obvious.

I paddled out in the morning with a functioning rudder and renewed resolve. I paddled another five days with an ever-growing sense of self and burgeoning confidence in my abilities to persevere. One day in the Gulf of Mexico, the water looked like the heavy seas, but I paddled on. I was in the Bay of Ten Thousand Islands, but I could tell with my map and compass which islands were which.

I never had to reach out to my dad again, but I never stopped sensing him there with me. It was surreal to be alone in the wilderness, yet feel so intrinsically connected to him.

Through our two beating hearts, I realized that even when I was alone, I would never really be alone—satellite technology or not. I knew he was seeing my journey through eyes that know me, and the feeling of being wholly understood and loved was all the protection and guidance I’d ever needed. I didn’t get lost again.

I pulled my kayak up onto the dock where the journey had begun some seven days and a hundred miles before, and pressed the button on my satellite communicator to signal a safe arrival back in civilization. As I unloaded my gear from the kayak, I turned my phone back on for the first time in a week. Notifications from my city life began to pour in, but I skipped through them to a message from my dad:

Yeah! That’s my girl. Congratulations on completing a great quest. I have followed your progress every day and I think you are awesome. Nicely done! You must feel pretty good about now. Talk soon. I love you.

After a shower, some grub and a cold brew, I called my dad. With laughter, we both shared our sides of the story of that time I got lost in the Everglades—me fumbling through brief messages from the middle of the water, and him from his office in the middle of a meeting with a client, showing the client the satellite map of where his daughter was off on her adventure.

As equals, our stories of that day blended into us swapping wilderness stories in general. We chatted for hours as the experience of all I’d just been through solidified within me. The trip had forever changed me in some of the greatest ways, and there I was talking with the man in my life who had pushed past his own fears of it to find the courage needed to become one of its greatest supporters.

Later, my dad would write in our journal:

After you were safe and sound, I realized how dialed in and intense I had been. I felt a little nauseous and spent. But I was mighty proud of you for handling adversity. It is these moments, when your mettle is tested, that shape you and strengthen you.

I knew you’d be a better wilderness person because of it…I worried less after that day. I knew you had what it took and would be fine. I still watched all the time and felt the glory of where you were.

The depth of our relationship is one of the greatest delights of my life. I can’t wait to see what’s next for my intrepid daughter.

Fathers, let your daughters be brave. Let yourselves be vulnerable. Because if you’re a good man, a good dad, that means you’re already there to protect them and guide them—even when you’re not.

To ALL women I say this:

To ALL women I say this: